Angry young men

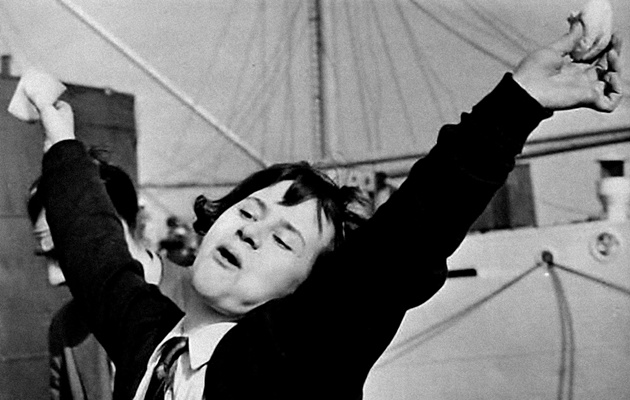

After last year’s editions of Spaghetti Westerns and Camp Films, presented as part of the Phenomena section, it is time to introduce another portion of non-mainstream cinema. This time, we will present the Angry Young section. It is a trend in British literature and cinema that was born in the 1950s and 1960s. The direct starting point for that trend was a literary manifesto, titled ”Declaration”. The idea for the group’s name came from a play by John Osborn — Look Back in Anger, which had its premiere in 1956. The movement was a response to the French New Wave. The concept behind the Angry Young was to break the modern problems into their constituent parts, showing the true and “naked” world.

Free Cinema was the first organisation that emerged from the foundations sparkling with revolt. It was open to the directors who created documentary forms. It formed the basis for the first films: Momma Don’t Allow (Karel Reisz, 1955), telling a story of young partying Londoners, or Every Day Except Christmas (Lindsay Anderson, 1957) about the life and work of salesmen. It was a cinema that showed the true face of England — this was the country that the young wanted to see. The more they got into it... the more soiled the images became. The shots started showing run-down districts and factories, symbolising the places of social oppression.

The Angry Young Man ignored the traditional means of expression, broke the ties with tradition and history and gave up the perfection of editing and acting. They opted for a spontaneous camera work and hiring untrained actors, instead of the professional ones. It was a cinema of young filmmakers, who intended to make a clear distinction between the things showed by the classic, studied and polished cinema and the things that lay dormant in their restless souls. It can be said that the stories presented by the Angry Young Man were a cry and manifestation. In a way, it was a didactic trend that tried to draw attention to the problems faced by the society, in troubled times. The aim of the cinema was to eliminate formulas, expose the duplicity of the system and show the naked and often unpleasant truth about the world. The centre of the plot was the lead character, an individualist, who served as a certain symbol — an everyman.

Therefore, the British filmmakers offered an all-purpose product, presenting the audiences with a peculiar mirror. They were the voice of their generation. Such cinema touched the most painful issues, presented complicated interpersonal relations — predominantly related to love affairs. Women were emancipated, often portrayed as artists and restless souls. No wonder, as that trend was largely influenced by the newly formed social ideas that freed people from the narrow frames imposed by history. The Angry Young Man were influenced, both by the feminist and socialist ideas. It was an introvert cinema, which took delight in the penetrating of the recesses of human existence. The French existentialism was another idea that left its mark on the trend, radiating on the entire Europe. The British artists promoted the ideas of freedom, the essence of everyday life, dignity of life and respect for human life.

The first film that made a direct reference to the demands of the Angry Young Man was Look Back in Anger (1958), by John Osborne. The main hero is an intellectual, who does not accept the rules of the world he has to live in. The film was made by Tony Richardson.

The most prominent film of that era was another of Richardson’s films — The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962). The leading character was probably most accurate in the depicting of the features that characterised a typical film of the Angry Young Man era. Colin Smith was a boy from the lower class, who did not like the disproportion between the place where he lived and the wealth of immoral bourgeois — he desired freedom and liberation. He was arrested for robbery and subjected to rehabilitation in a childcare centre. There, he took part in a long-distance run, against both the members of an exclusive secondary school and his headmaster.

Both films will be presented during TOFIFEST. However, it is just a foretaste. We would like to invite you all to see: Taste of Honey (also by T. Richardson), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (K. Reisz), A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar (both by J. Schlesinger), as well as This Sporting Life (by L. Anderson).

Also in this section

- Idea

- Sections

- Awards

- Volunteers

- Archive